Global News

- Details

- Category: Global News

In a peer-reviewed workshop report on biodiversity and climate change published earlier this month, global experts identify key options for solutions in first-ever collaboration between IPBES and IPCC selected scientists. The report highlights a number of instances in which climate change and biodiversity loss are key interacting issues for mountain regions.

Unprecedented changes in climate and biodiversity, driven by human activities, have combined and increasingly threaten nature, human lives, livelihoods and well-being around the world. Biodiversity loss and climate change are both driven by human economic activities and mutually reinforce each other. Neither will be successfully resolved unless both are tackled together. This is the message of a workshop report, published earlier this month by 50 of the world’s leading biodiversity and climate experts.

- Details

- Category: Global News

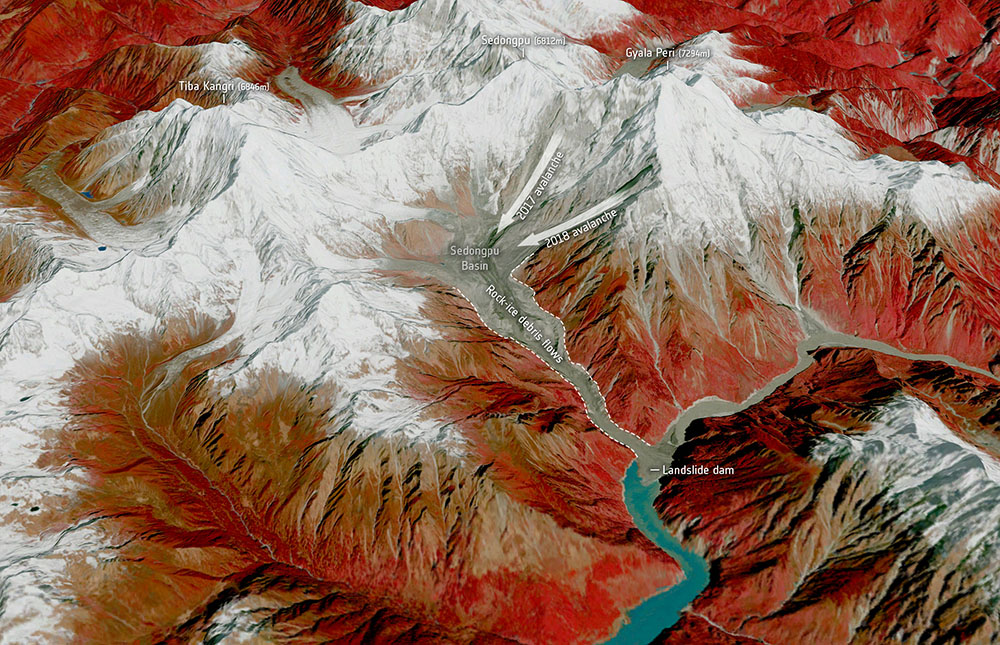

Some four months ago, a devastating flood ravaged the Chamoli district in the Indian Himalayas, killing over 200 people. The flood was caused by a massive landslide, which also involved a glacier. Researchers at the University of Zurich, the WSL and ETH Zurich have now analyzed the causes, scope, and impact of the disaster as part of an international collaboration.

On 7 February 2021, a massive wall of rock and ice collapsed and formed a debris flow that barreled down the Rishiganga and Dhauliganga river valleys, leaving a trail of devastation. The flood took more than 200 lives and destroyed two hydropower plants as well as several roads and bridges. A large international team including researchers from the University of Zurich (UZH), the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) and the ETH Zurich came together immediately after the disaster and began to investigate the cause and scope of the flood and landslide. Their study used satellite imagery, digital models of the terrain, seismic data and video footage to reconstruct the event with the help of computer models.

- Details

- Category: Global News

With global warming decreasing the size of New Zealand’s alpine zone, a University of Otago study found out what this means for the altitude-loving kea.

The study, published in Molecular Ecology, analysed whole genome DNA data of the kea and, for the first time, its forest-adapted sister species, the kākā, to identify genomic differences which cause their habitat specialisations.

- Details

- Category: Global News

New research based on information from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat mission shows how much ice has been lost from mountain glaciers in the Gulf of Alaska and in High Mountain Asia since 2010.

As our climate warms, ice melting from glaciers around the world is one of main causes of sea-level rise. As well as being a major contributor to this worrying trend, the loss of glacier ice also poses a direct threat to hundreds of millions of people relying on glacier runoff for drinking water and irrigation.

- Details

- Category: Global News

One tends to think of mountain glaciers as slow moving, their gradual passage down a mountainside visible only through a long series of satellite imagery or years of time-lapse photography. However, new research shows that glacier flow can be much more dramatic, ranging from about 10 metres a day to speeds that are more like that of avalanches, with obvious potential dire consequences for those living below.

Glaciers are generally slow-flowing rivers of ice, under the force of gravity transporting snow that has turned to ice at the top of the mountain to locations lower down the valley – a gradual process of balancing their upper-region mass gain with their lower-elevation mass loss. This process usually takes many decades. Since this is influenced by the climate, scientists use changes in the rate of glacier flow as an indicator of climate change.

- Details

- Category: Global News

Research published this month in BMC Ecology and Evolution explores the link between the size of white dead-nettle flowers and pollinator size and, using population genetic analysis, suggests that large flower size evolved independently in populations on different mountains in Japan as a convergent adaptation to locally abundant large bumblebee species.

The morphological compatibility between flowers and insects was given in the famous textbook example of Darwin's orchids and hawkmoths. As in this example, many studies have shown that geographical variations in flower size match the size of insects in each region. In other words, studies have shown 'flower-sized regional adaptation' in which large flowers evolve in areas pollinated by large insects and small flowers evolve in areas pollinated by small insects.

- Details

- Category: Global News

The International Science Council invites comments on the Scientific and Technological Community Major Group position paper for the 2021 High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. We encourage the mountain research community to add a mountains perspective to this important document. Deadline 6 May 2021.

The International Science Council, together with the World Federation of Engineering Organizations (WFEO), leads the UN Major Group for Science and Technological Community (STC MG) for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Its mandate is to promote science and to strengthen the scientific basis of decision-making and governance of sustainable development.

- Details

- Category: Global News

An international research team including scientists from ETH Zurich has shown that almost all the world’s glaciers are becoming thinner and losing mass’ and that these changes are picking up pace. The team’s analysis is the most comprehensive and accurate of its kind to date.

Glaciers are a sensitive indicator of climate change – and one that can be easily observed. Regardless of altitude or latitude, glaciers have been melting at a high rate since the mid-20th century. Until now, however, the full extent of ice loss has only been partially measured and understood. Now an international research team led by ETH Zurich and the University of Toulouse has authored a comprehensive study on global glacier retreat, which was published online in Nature on 28 April. This is the first study to include all the world’s glaciers – around 220,000 in total – excluding the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. The study’s spatial and temporal resolution is unprecedented – and shows how rapidly glaciers have lost thickness and mass over the past two decades.