A global survey by the MRI Mountain Governance Working Group sheds new light on how mountain regions connect governance with spatial planning. The findings reveal substantial gaps between high-level agendas and their implementation on the ground, shaped by varying technical capacity, participation, and planning instruments.

The Mountain Research Initiative’s (MRI) Mountain Governance Working Group (MGWG) conducted a global mountain governance survey earlier this year. The MGWG received responses from 20 mountain areas worldwide, with 40% coming from European Alps and the rest representing key mountain ranges such as The Andes, The Rockies, The Hindu-Kush Himalayas and Tibet. Respondents were contacted either through the MRI Expert Database (academics and practitioners) or directly through a curated list of potential respondents. In addition, the survey was disseminated through peer organisations.

The extended survey featured 15 sections, including five new ones that focused on spatial planning, Geo/GIS databases, financial instruments, international environmental instruments, and groundwater resources. The latter will be addressed separately as a specific topic. The remaining ten governance sections were carried over from the first edition of this survey (Tucker et al. 2021). This short article highlights insights from the new sections in connection to mountain governance. Initial insights were also shared at the MRI Governing Body retreat at the Swiss village of Curaglia (Medel), and at the International Mountain Conference (IMC25) in Innsbruck during a joint science-policy workshop on regional mountain governance (with the Alpine Convention, ISCAR, Carpathian Convention, CONDESAN, ARCOS, UNEP, and MRI).

Core Governance Challenges Across Mountain Regions

Based on weighted responses, it is no surprise that climate change, natural hazards, and water related issues – in addition to other critical political and socioeconomic factors – emerged as major governance challenges that impede environmental sustainability to varying degrees. Tensions and conflicts over land rights and land scarcity also ranked as high priority and widely shared concerns, which are inconsistently addressed across different mountain regions. The MRI MGWG plans to call for further discussion on the former at the World Biodiversity Forum (WBF26) in Davos during the workshop Tenure for Nature: Why Land Rights Matter in Biodiversity Governance. Other issues related to deforestation, glaciers, desertification, disaster risk, land use practices and other challenges, vary depending on their prevalence and overall contexts of each mountain area.

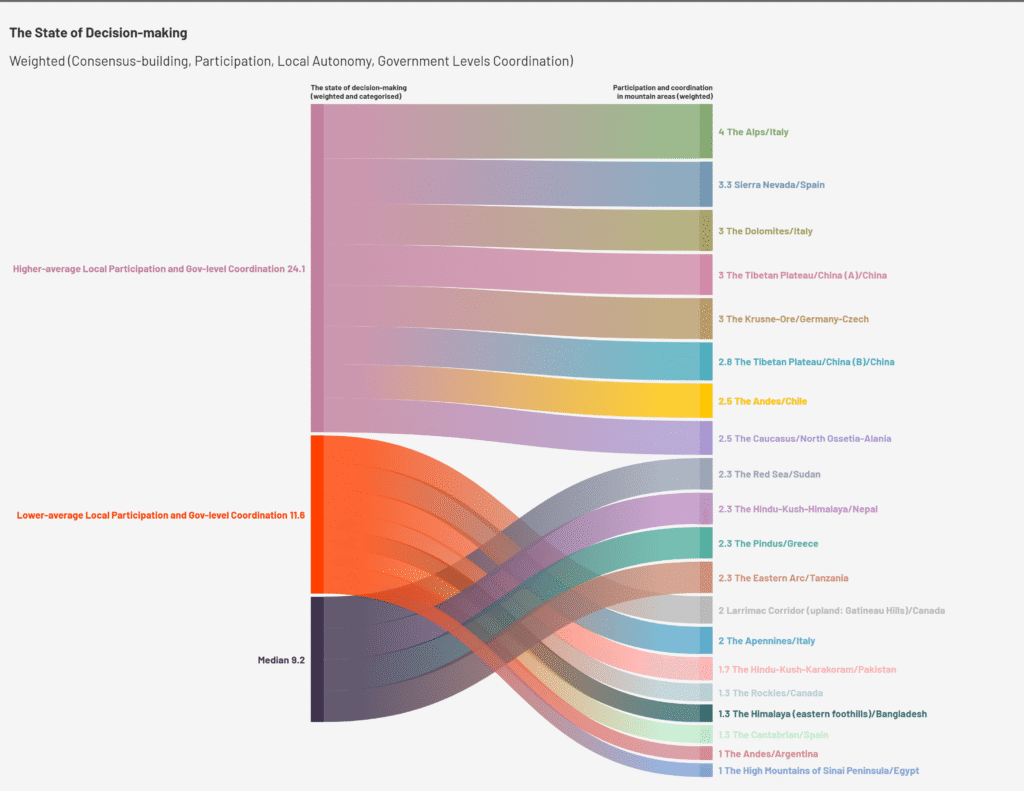

The state of decision making around the above governance challenges in terms of local consensus-building, participation, autonomy and/or coordination between government levels strongly influences how the 20 mountain areas scored on all other issues (Figure 1). In other words, there is a certain correlation between levels of participation and coordination and all other facets of governance and spatial planning. Forty percent of the surveyed mountain areas scored above the median in this regard.

Spatial Planning Gaps and the Strategy–Implementation Divide

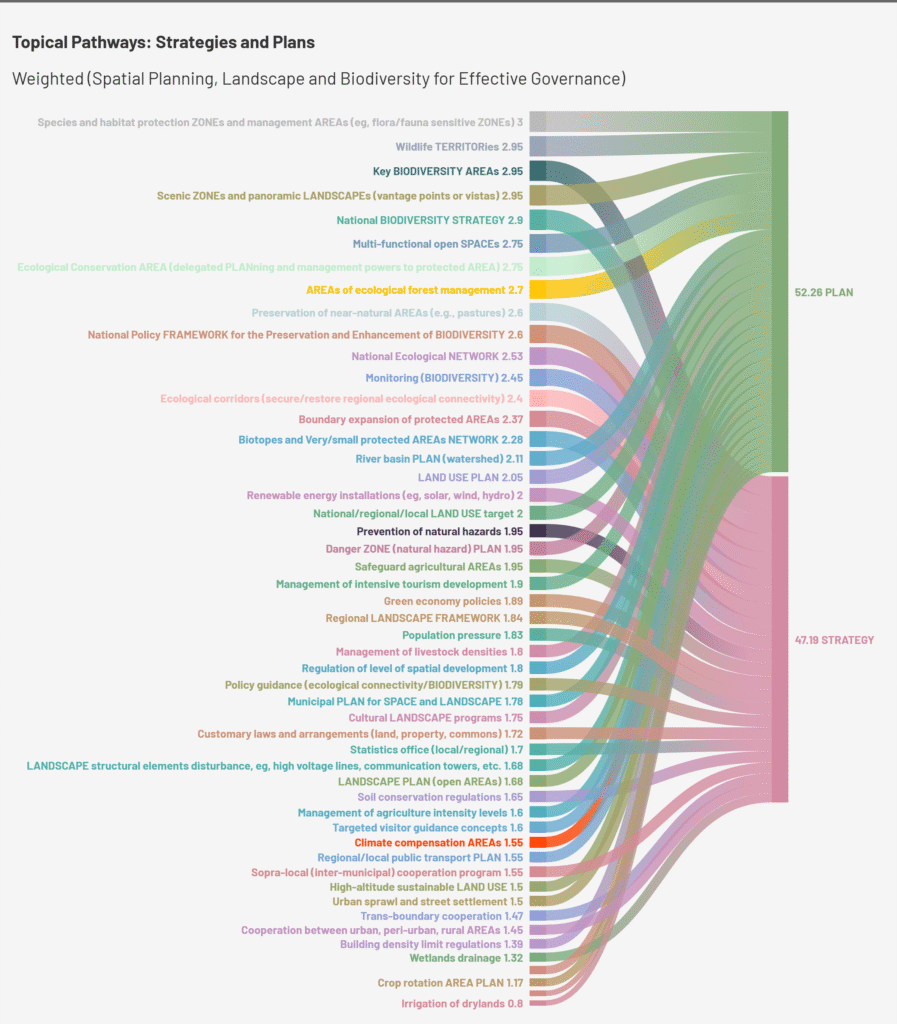

Categorising and drawing a clear line between strategies and plans is not always straightforward. Insights from nearly 50 topical pathways assessed under ‘spatial planning, landscape and biodiversity’ confirm a major global mountain governance concern: high-level or widely rectified agendas, strategies, frameworks, or environmental agreements (international, supranational, and national) are not matched by well-developed planning instruments at regional and local levels. For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which has 168 signatures out of 196 parties and recognises the importance of mountain ecosystems for biodiversity conservation, is not consistently associated with landscape and land-use planning instruments in practice (UNEP 1993). These instruments reflect the local and regional execution of global policies in mountain areas (Figure 2). This gap is not only visible when comparing mountain ranges across continents but also within single countries, such as across the Italian Alps, Dolomites, and Apennines.

Mountain areas with the highest weighted scores across all 50 instruments also rank highest on the state of decision making. These include areas in the Italian Alps and Dolomites (vs. the Apennines), the Spanish Sierra Nevada, Chinese Tibet, the German-Czech Krusne-Ore range, Chilean Andes, and the Caucasian North Ossetia-Alania.

Uneven Geo/GIS Data Availability

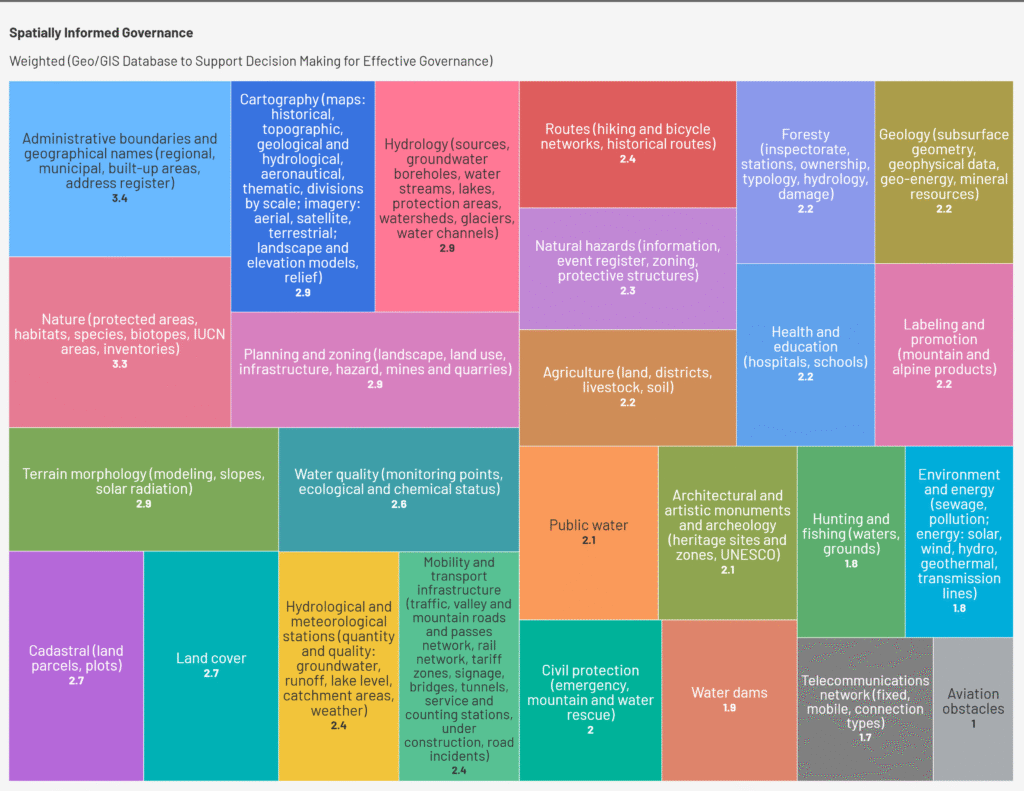

A divide also exists in the availability of the geo/GIS databases to support spatially informed mountain governance. A clear contrast exists between the highly available data layers for the physical environment, which are sourced from international, supranational and/or national organisations, and the inconsistent availability of the regional planning and management data, which often depend mainly on in-situ technical expertise (Figure 3). Several regions in the Central Alps bridge this gap through regional funding and strong technical capacity in-situ, with their geo/GIS databases complemented by the ordnance, geological, hydrological, and similar survey organisations (national), as well as European Union databases (supranational). Globally, many countries rely predominantly on national organisations, coupled with shortages in local or regional technical expertise.

This divide is clearly reflected in the major gap between strategies andplans and is influenced by the state of decision making. Mountain areas with established geo/GIS databases tend to have more informed planning instruments in place. Spatial data should therefore be viewed from an integrative perspective, with the relevance of datasets varying according to local/regional governance and planning contexts and challenges. A definition for geo/GIS databases has been discussed and refined through several iterations at the Alpine Biodiversity Conference and Forum Alpinum in the Slovenian town of Kranjska Gora (Julian Alps), ensuring connectivity between the core Alps and their surroundings in the workshop: ‘Integrate the use of up-to-date spatial information, spatial data visualisation and modelling (e.g., maps, GIS) into decision making’.

Financial Instruments and Local Governance Capacity

The diversity of financial instruments for land resource management and biodiversity conservation at municipal/local and regional levels is equally important, and essential to empowered and decentralised effective governance systems. For example, Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) (30%), funds to preserve landscape elements (30%) or tradeable land use permits (30%) are not widely accessed on local and regional levels across mountain areas, especially when compared to more conventional instruments such as land use tax (40%), building land development fees (35%), and funds for decentralised technical infrastructure (energy, water, waste, etc.) (35%).

Scientific researchers were ranked the fourth most important actors in mountain areas (40%), after the three levels of spatial governance — regional (50%), followed by local and national (44% each).

Linking Spatial Planning and Effective Governance

In conclusion, effective mountain governance connected to spatial planning depends strongly on local participation and coordination and the availability of planning and financial instruments, supported by technical data and in-situ expertise. These factors contribute significantly to the gap between the global agendas, strategies, frameworks, and environmental agreements and their actual implementation, and have a formative effect on the inconsistency in the ecological and social state of global mountain governance (Figure 4).

Ultimately, the use of spatial planning in connection to governance varies considerably between global mountain areas based on its purpose. This includes, but is not limited to, implementing state objectives (top-down approach) or ensuring local community development (bottom-up approach), and/or facilitating access to resources from external actors or establishing initial inventories and visualizations that indirectly influence governance processes.

If you are interested in participating in the MRI Mountain Governance Working Group or learning more about it, please visit our website or join the mailing list here.

References

Tucker, C. M, I. Alcántara-Ayala, A. Gunya, E. Jiménez, J. A. Klein, J. Xu, S. Bigler. 2021. Challenges for Governing Mountains Sustainably: Results of a Global Survey. Mountain Research and Development 41(2). https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-20-00080

UNEP. 1993. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/convention

Cover photo: The town of Saint Katherine at el-Melga Plain in Sinai Peninsula 1,600m ASL (the only mountain town in Egypt). It is located in a protected mountain area featured in the MRI MGWG survey and faces exponential governance and spatial planning challenges as a result of a new mass tourism project. Photograph by Ahmed Shams from Gebel Abbas Basha 2,304m ASL, 14 August 2015.